In the

summer and fall of 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt confronted

wars in both Europe and

Asia. In Europe, a remilitarized Nazi Germany dominated most of the

continent and threatened to complete its domination with the capture

of Moscow and by bludgeoning England into submission. In Asia, Japan

was not only continuing its conquest of China, it had moved into

French Indo-China. There was little Roosevelt could do directly to

halt either war. The ability of a president to make policy decisions

is limited by the extent to which he can convince the American public

to support him. Since American public opinion at that time would not

support a declaration of war in either Europe or Asia, all Roosevelt

could do was support England with liberalized trade, and impose

economic sanctions on the Japanese. If those sanctions failed,

however, more direct military action might prove necessary. Roosevelt

hoped the sanctions would prove so burdensome to the Japanese that

they would lead to renewed talks about a peaceful solution, but at

the same time, he also understood America must be prepared to accept

war if Japan so chose.

In September of 1940, Roosevelt stated the American policy toward the

growing conflict in Europe and the Pacific, “I stand…as President

of all the people, on the platform… ‘We will not participate in

foreign wars, and we will not send our army, naval or air forces to

fight in foreign lands outside of the Americas, except in case of

attack’.” Sixteen days later, Germany, Italy, and Japan signed

the Tripartite Pact, creating an alliance and the birth of the Axis

Powers in the upcoming Second World War. There was now a dual threat

in both the European and Pacific Theaters which posed an even greater

threat to the United States. Roosevelt wrote to Ambassador to Japan

Joseph C. Grew, in response to the Tripartite Pact that the United

States is “engaged in the task of defending our way of life” and

“Our strategy of self-defense must be a global strategy which takes

account of every front.” In the aftermath of this alliance, it

became ever clear the policy of appeasement had failed in Europe and

was not working in Asia. Regarding the Pacific Theatre, the Empire of

Japan secured Manchuria in 1931, invaded further into China in 1937,

later becoming known as the Second Sino-Japanese War, and occupied

French Indo-China in 1940. From this point forward, tensions between

the United States and Imperial Japan became increasingly dire.

Correspondence between the two nations shows, on both sides, that an

understanding and agreement needed to be made in order to prevent an

open conflict. In response to the Tripartite Pact, Roosevelt ended

the exportation of all scrap iron and steel to Japan.

|

| Pre WWII Japanese propaganda "Japan Has Woken Up" |

To

understand the policies of the Japanese Empire, one must understand

how their culture had a profound impact. Japan, at this time, was a

proud and traditional country, and when Japan transformed from a

feudal society believing in isolationism to an industrial war-machine

bound on expansion, there was much strife and disagreement among the

population. According to historian Stephen Pelz, “During the feudal

period, an inferior had been able to make a public protest only on

pain of death; therefore, when conditions became intolerable, the

loyal samurai would commit suicide, thereby hoping to induce his

master to self-reflection.” This perverse traditional style carried

over into the transformation of Japan and quickly became a method to

showcase the disapproval of their leaders. This “suicide for a

cause”, along with political assassinations, were the methods of

choice used to succeed in their ultimate goal of having the army and

the navy take control of the government and away from the

politicians. These demonstrations of disapproval were predominately

conducted by young members of the military to instill fear in the

Japanese high command. Fear of assassinations caused the “influential

group around the Emperor…to keep their lord safe by appeasing the

military.” This split the nation into two factions: the treaty

faction, who favored diplomacy, and the military faction which sought

confrontation.

The

military faction eventually accomplished its goal of controlling both

the army and the navy through intimidation, and as a result, began

Japanese expansion by invading Manchuria in the fall of 1931.

However, the treaty faction still controlled the Foreign Office which

determined diplomatic dealings with other countries such as the

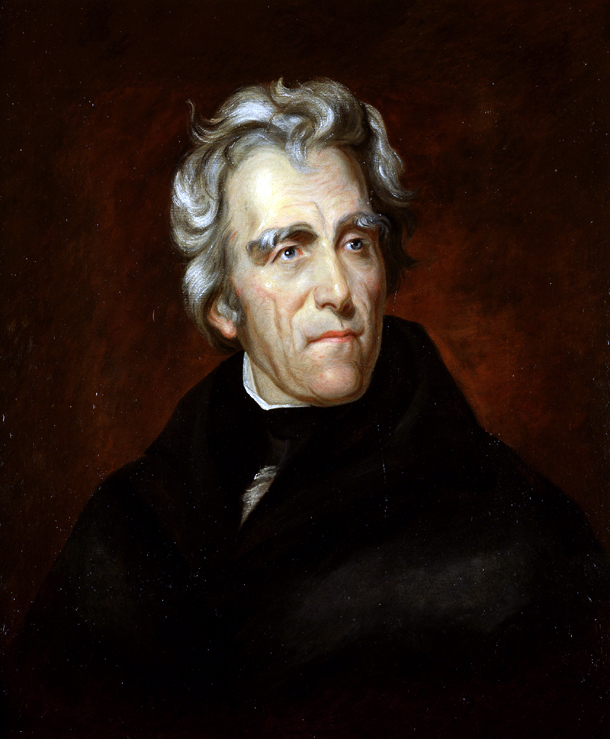

United States. The Japanese Ambassador to the United States,

Kichisaburo Nomura, was a member of this treaty faction,

and as a

result, was never in the full loop of the decisions being made back

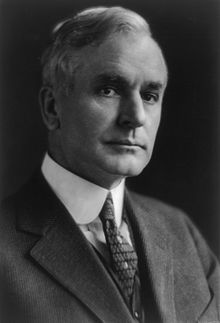

in Japan. Thus, while President Roosevelt and Secretary of State

Cordell Hull heard one thing from Nomura, they were seeing different

results from Japan. This military faction used this to their

advantage. While Nomura fed Roosevelt and Hull with promises of peace

and justified occupation, the army and navy continued their military

conquest of the South-Western Pacific.

|

| Kichisaburo Nomura |

|

| Cordell Hull |

On

July 24, 1941, the same day the Japanese invaded and occupied French

Indo-China, Acting United States Secretary of State Sumner Welles met

with Japanese Ambassador Nomura. Nomura told him that the military

occupation of French Indo-China was, “to assure to Japan an

uninterrupted source of supply of rice, and other food stuffs” and

“the need for military security.” On the very same day, at the

41st Liaison Conference, Minister Soemu Toyoda, who supported the

military faction, declared, “I would like to get the United States

to understand that the present occupation of French Indo-China is not

a military occupation, but something that is based on the Empire’s

need and was arranged after agreement with the French.” This

“agreement with the French” however, was with the French Vichy

Government which had just been installed as a puppet head of state

following the German occupation of France in the summer of 1940. The

Japanese presented similar justifications for the occupation of

Manchuria. Their real ambition was to acquire natural resources -

especially coal and iron ore.

In

defense of their occupation of French Indo-China, Ambassador Nomura

argued the Japanese could not withdraw without “losing face”. The

Japanese belief of “face” coincided with a person’s reputation

and honor, and how they were perceived by others. To leave French

Indo-China directly after occupying would bring shame and

embarrassment to the government. President Roosevelt questioned

Nomura asking if Japan occupied French Indo-China “due to German

pressure upon Japan?” This was a very formidable argument for

Roosevelt to present, for he believed Japan felt threatened by how

much progress Germany was making in Europe.

The

basis for Roosevelt’s idea dates back to when, in the early 1930’s,

Hitler began exercising German dominance in Europe and by 1941, had

already occupied the Rhineland, annexed Austria, taken

Czechoslovakia, conquered Poland and France, invaded Russia and was

knocking on Moscow’s door. Hitler had taken Germany from the depths

of depression and turned her into a world power in a fraction of the

time it took Japan since she emerged as a world power at the

conclusion of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905. Roosevelt thought

wrong. The military faction, who by this time was in control of the

government, actually admired how well Germany made progress in Europe

and sought to bring a parallel in the Pacific.

Due to European Colonialism, many of the countries in

Europe owned territory in the Pacific. As Germany steamrolled through

Europe, it left many targets available for the Japanese to move in

and conquer virtually unopposed, territories such as French

Indo-China, the Netherlands East Indies, and British Malaya.

President Roosevelt, however, did not understand why military force

needed to be used. This same military force was responsible for the

genocide in the Rape of Nanjing which became part of a campaign the

Japanese called the China Incident. The fact that the Japanese called

it the China Incident shows their intention to appear to the world as

a peace seeking nation, and not the imperialistic nation for which it

really was. The Japanese began to murder on a mass scale. In two

months during the Rape of Nanjing, “Japanese soldiers raped seven

thousand women, murdered hundreds of thousands of unarmed soldiers

and civilians, and burned one-third of the homes in Nanjing. Four

hundred thousand Chinese lost their lives as Japanese soldiers used

them for bayonet practice and machine-gunned them into open pits.”

|

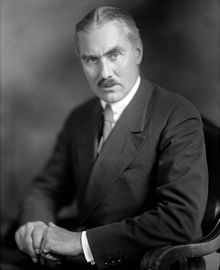

| Henry L. Stimson |

In

the very same month, the Japanese were also responsible for the

sinking of the U.S.S. Panay.

The Panay was an

American gunboat on a river near the town of Nanjing that was

attacked by Japanese bombers even though she was clearly marked with

three separate American flags. This incident was resolved by “the

acceptance of an indemnity of $2,214,007.36.” A critic of

Roosevelt’s policies toward Japan, historian Charles C. Tansill

claims, “The whole matter had been handled with admirable restraint

by the officials of both countries. It is greatly to be regretted

that this pacific spirit soon faded away.” Tansill believes

Roosevelt and his cabinet intentionally forced Japan into a situation

where they felt compelled to attack in order to bring about the

United States entry into World War II. Tansill quotes Secretary of

War Henry L. Stimson, who wrote in his Diary

on November 25, 1941, “The question is how we should maneuver them

into the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much

danger to ourselves.”

It

became clearer that Japanese intentions during the China Incident

were not just for resources, but there was little to nothing

Roosevelt could do to intervene. The United States, at that time, was

still in the midst of recovery from the Great Depression, and public

opinion, which desired to stay out of a foreign war, would not

tolerate any intervention.

The

day after the Japanese invaded French Indo-China, Roosevelt froze all

Japanese assets in the United States, essentially ending most trade

between the two nations. Since the United States supplied much of the

raw materials needed by the Japanese war-machine, Roosevelt severely

limited the Empire’s ability to expand. His hope was that Japan

would stop its expansionist program and resume a free and openly

based form of trade in the Pacific. In correspondence between the

American Ambassador to Japan, Joseph C. Grew, and the President, Grew

warned Roosevelt of the impact an oil embargo would have. It would

cause Japan to invade the Dutch East Indies to which the President

replied, “Then we could easily intercept her fleet.” This

response from Roosevelt makes historian Tansill believe, “he was

thinking in terms of war with Japan.” However, this conversation

between Roosevelt and Grew took place in September of 1939, long

before the Japanese invaded French Indo-China, economic sanctions

were used, and a diplomatic solution still seemed attainable.

Excluded

from these sanctions was the much needed resource of oil. Before the

Japanese invaded French Indo-China, Roosevelt was in a particular

bind. He did not want to stop the exportation of oil to Japan, and

even acknowledged that discontinuing the exportation of oil to the

Japanese would force them to move into the Netherlands East Indies to

fulfill their determination to become economically self-sufficient.

In a meeting with Nomura, President Roosevelt explained the reasons

for the exclusion of oil. It was because the United States

recognized, “that if these oil supplies had been shut off or

restricted the Japanese Government and people would have been

furnished with an incentive,” to invade the Netherlands East Indies

and, “assure themselves of a greater oil supply than that which,

under present conditions, they were able to obtain.” This exclusion

of oil was then an effort to continue diplomatic relations with the

Japanese in hopes of a peaceful solution.

The

later addition of oil to the sanctions came about because Assistant

Secretary of State Dean Acheson assumed that the decision to include

oil among the embargo items had already been made. He therefore

publicly announced the freezing of assets was an “embargo”

against the Japanese Empire. But, according to historian Herbert

Feis, “he did not explain how far short of one it would be.” The

public greeted this statement with approval thinking Roosevelt had

cut all ties of trade with the Japanese. The British and the Dutch

followed shortly after with their own embargoes on Japan and, within

a matter of days, Japan lost 90 percent of its oil imports. Though

Roosevelt did not want this policy carried forward, he did not speak

out and bring clarity to Acheson’s assumptions. There are two

primary reasons for this. The first was that the overall reaction

from the general public to this announcement was positive. Moreover,

if he reversed what had been done, Roosevelt and his cabinet would

appear as if they had surrendered to Japanese aggression. He now had

public approval to go forward with a policy that was more vocal

because it was backed by the people of the United States. By this

point, Roosevelt knew the Japanese war-machine’s true intentions.

Careful reading of the multiple proposals for peace by the United

States after the Japanese invaded French Indo-China, suggested an

ultimatum was set in which the Japanese must stop their expansionism

or the United States would intervene to protect American interests in

the Pacific. Such a policy as this was one the Japanese would not

accept. Historian Jonathan Utley claims this embargo, “placed a

time limit on peace in the Pacific.”

Both

Roosevelt and Welles acknowledged and sympathized with Japan’s

quest for natural resources, but resented the manner in which they

did it by military force. In explaining the American policy to

Japanese Minister, Mr. Kaname Wakasugi, in a meeting August 4, 1941,

Welles told Wakasugi that the policy of the United States had been

made perfectly clear in letters “exchanged between the Secretary of

State and the Prime Minister, to public statements made by the

Secretary of State and by the President and other officials.” He

declared that Japan’s policy was deemed, “intolerable by the

United States,” and if Japan’s military conquest continued it

would, “inevitably result in armed hostilities in the Pacific.”

Less than two weeks later, Roosevelt explained to Ambassador Nomura

that if Japan expanded any further into the Pacific “by force or

threat of force,” the government of the United States would, “take

immediately any and all steps which it may deem necessary toward

safeguarding the legitimate rights and interests of the United States

and American nationals and toward insuring the safety and security of

the United States.”

|

| Joseph C. Grew |

Joseph

C. Grew, was the best kept secret of American policy in dealing with

Japan prior to the outbreak of war. Assuming his ambassadorial duties

to Japan in 1932, Grew saw first-hand the actions, policies, and

intentions of the Japanese Empire. He foresaw the growing threat of

the Japanese and warned Roosevelt and his staff of the impending

conflict that would stem as a result thereof. He wrote Roosevelt a

year in advance of the attack at Pearl Harbor that, “we are bound

to have a showdown someday” with Japan and he questioned whether or

not it was in America’s best interest to have this showdown,

“sooner or to have it later,” Grew claimed Japan had become one

of the “predatory nations…which aims to wreck about everything

that the United States stands for.” He also believed the economic

sanctions on Japan would, “seriously handicap Japan in the long

run,” but that these sanctions only reinforced Japan’s idea of

making herself economically self-sufficient. Taking all these factors

into consideration, Grew believed the problem with Japan should be

dealt with immediately because, “the principal point at issue…is

not whether we must call a halt to the Japanese program, but when.”

Grew’s

insight was extremely valuable to President Roosevelt and Secretary

of State Cordell Hull, for Grew was the eyes and ears of the United

States. In a telegram to Hull, dated January 27, 1941, Grew wrote,

“the Japanese military forces planned, in the event of trouble with

the United States, to attempt a surprise mass attack on Pearl Harbor

using all of their military facilities.” Grew learned of this from

a colleague, who deemed it was important enough to tell him after

hearing it from multiple sources of information. Only two months

later he wrote to Hull that over the weekend in the main streets of

Osaka, “anti-American, British, and Chinese posters have been

observed,” and they contained “crude caricatures of Churchill,

Roosevelt, and Chiang Kai-Shek being struck by a hammer and the

caption in translation, ‘Strike the enemies of the Imperial

nation’.” Grew’s point to Roosevelt and Hull was that if either

the United States or the Empire of Japan continued their course of

action, it will become inevitable in some point of time that a

military conflict will arise. Grew then revealed the propaganda being

used by the military faction in a telegram to the Secretary of State.

“Japanese press continues to emphasize economic encirclement by

American and British in form of freezing orders and export bans and

Japan’s preparedness against all eventualities.” The Japanese

Empire believed the American policy in regards to their expansion was

to contain, and control their empire, through coercion, by the use of

sanctions - which was not entirely false. By this point, Roosevelt

was using these sanctions to put pressure on the Japanese Empire in

hopes of a peaceful settlement.

Correspondence

from Grew to Hull in the latter months of 1941 described how the

embargo on Japan and the freezing of assets have taken its toll on

the Japanese economy. Grew reported an “increasing seriousness”

in the economic situation, and that multiple reports pointed towards

a “progressive decline” in the industrial production on goods due

to the “scarcity” of supplies and a skilled labor force. Grew

then labeled the international financial position as, “embarrassing.”

|

| Operation MAGIC |

As

November drew to a close, tensions between the two nations grew.

Conspiracy theorists argue that, by this time, the United States had

cracked the Japanese diplomatic code through

a program called MAGIC; an allied cryptanalysis program used to

decipher Japanese code, and had known of the impending Japanese

attack at Pearl Harbor. This is the backbone of the “Back Door”

argument on how Roosevelt let the Japanese attack the United States

at Pearl Harbor. Historian Mark A. Stoler argues, “American

cryptographers had indeed broken the Japanese code, but it was their

diplomatic code, not

any army or navy code. Consequently, Roosevelt and his advisors knew

from MAGIC that a Japanese attack was imminent if agreement was not

reached by November 29.” This agreement was of a diplomatic nature

and therefore, alerted the United States of an attack, but, “they

did not know where that attack would take place or what the overall

Japanese war plan was... and Japanese troop ships had been spotted

heading south.” This led Roosevelt to believe the Japanese planned

to attack either the Dutch East Indies or the Philippines, well away

from Pearl Harbor.

One viable option for Roosevelt in response to these

rapid troop movements, was to challenge the Japanese command and call

for an immediate stop to it, but instead, on November 27, he issued a

“war warning” to the American commanders in the Pacific. If

Roosevelt had contacted the Japanese command and demanded them to

cease all troop movements, it would have alerted the Japanese to the

American penetration of their diplomatic code. Grew issued Hull

another warning in mid-November, emphasizing a “need for guarding

against sudden military or naval actions by Japan,” and that the

Japanese would, “exploit all available tactical advantages,

including those of initiative and surprise.” However, Grew made

clear that the United States should not

give prior warning because the “control in Japan over military

information” is “extremely effective.” This suggests that Grew

may have believed that lives lost in a surprise Japanese attack would

be outweighed by the overall benefits of knowing the Japanese

diplomatic code.

The

letters and correspondence from Roosevelt, Welles, and Hull all

suggest that when in communication with the Japanese heads of state,

the intention was to find a peaceful diplomatic solution. It was the

Japanese policy of ‘Expansion by Force’ that brought about the

attack at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, December 7, 1941. There is no

evidence to support the claim that Roosevelt purposely tightened the

screws so hard on Japan economically, that it forced them to attack.

All of Roosevelt’s policies were conducted in response to Japanese

aggression in the Pacific. Yes, Roosevelt could have publicly

announced that oil would not be a part of the sanctions against

Japan, reversing Acheson’s announcement, but with public opinion

turning to an anti-Japanese mood after the invasion of French

Indo-China, Roosevelt used this to his advantage. It was clear to

him, by that point, the intentions of the Japanese and their need to

expand.

With

the military actions of the Japanese, the failure of diplomatic

negotiations, and the oft-repeated warnings from Grew, it was only a

matter of time before the Japanese attacked, and forced the United

States into the bloody conflict of World War II. Roosevelt and his

cabinet presented a very clear stance in their disdain for Japanese

aggression and pursuance of peaceful negotiations. The sanctions

Roosevelt employed had a drastic effect on the Japanese economy, but

the Japanese did not respond in the way Roosevelt would have hoped.

Instead, the Japanese invariably continued their expansion into the

South-Western Pacific. They showed a total disregard to the peoples

of that region, and eventually attacked the United States at Pearl

Harbor, Hawaii, bringing about the American entry into World War II.